Framing 'Violence', from the 2025 LA protests to the Israeli occupation of South Lebanon

On how 'violence' is reported on, from the Israeli occupation of South Lebanon to the 2025 LA protests

Hauntologies essays and articles are mostly free but some are paywalled. To gain access to all of this websites’ archives, please consider a paid subscription. By doing so, you will gain access to all the archives.

This will be a quick one.

The thing about monopoly of violence is, well, that the state has the monopoly on violence.

Journalism can be better at recognising that fact instead of wasting time talking about ‘violent protests'.

Civilians never have the monopoly on violence. The state does.

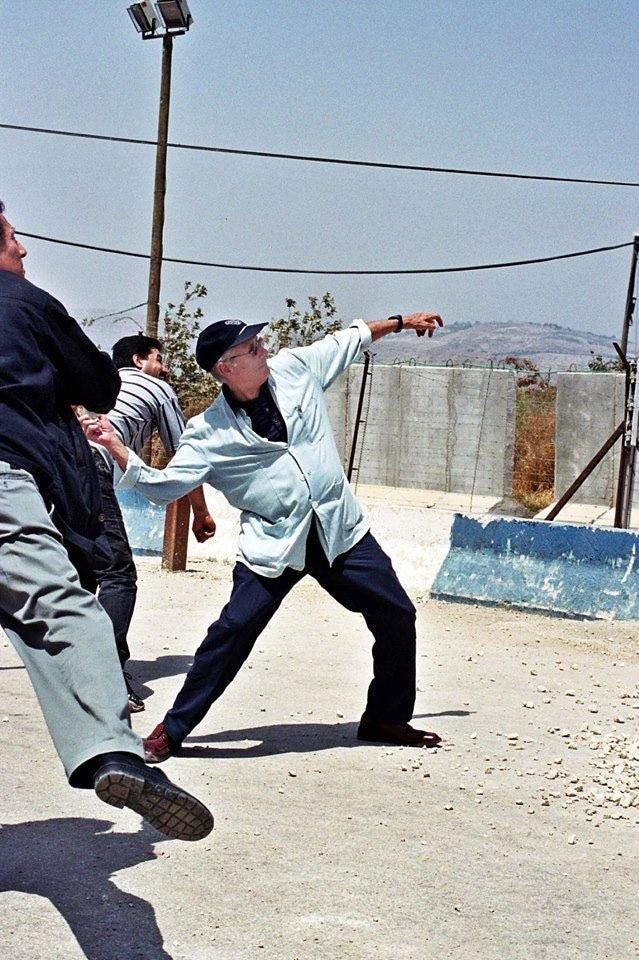

The same goes with unseen versus seen violence. You may think that some person with a rock at a protest is the violent one, but to do that you need to erase the daily mass violence inflicted by the state on citizens and non-citizens.

You need to be able to compare a rock thrown by a protester with tanks and jets and mass incarceration and ICE kidnapping children and border cops letting innocent people die of thirst and teargas and torture and more. If you erase the latter and only look at the …