The Stories We Tell

Tech oligarchs are coopting fictional universes to sell us a false story of their inevitability. To defeat them we need to reclaim the power of fiction to imagine a world beyond their grasp.

This article was first published in New Internationalist magazine. You can follow NI’s free weekly newsletter via the link: https://newint.org/newsletter

Hauntologies essays and articles are mostly free but some are paywalled. To gain access to all of this websites’ archives, please consider a paid subscription. By doing so, you will gain access to all the archives.

As this essay was already paid for by New Internationalist, I'm keeping it free here.

When US tech giant OpenAI released a new feature allowing users to turn themselves into Japanese anime characters in the style of Spirited Away creators Studio Ghibli, the backlash was swift. After all, Studio Ghibli’s co-founder Hayao Miyazaki is on record saying that AI tools are ‘an insult to life itself’.1 OpenAI’s blatant disregard for Miyazaki’s own wishes was part of the angry reactions, but it also proved, in the words of tech writer Brian Merchant, that ‘for the most adamant of AI advocates, “Ghiblification” is just more proof that they’ve won; that tech has conquered art, and that they can use and commodify it as they please’.2

Although the speed at which Big Tech is seeking to render art obsolete is very concerning and should be met with resistance, these attempts also reveal something unintentionally hopeful about current trends: they are dependent on the very artists they seek to replace. The development of tools like this ‘Ghiblification’ filter requires the theft of millions of frames of Ghibli movies made by artists who were neither asked, credited, or compensated for their work.

Colonizing imagination

This wasn’t the first time Big Tech has hijacked popular fictional universes for its own ends. Tech bosses have long fed off popular fictional worlds to legitimize their power. Billionaire Peter Thiel, for instance, has named his companies after Lord of the Rings references. Elon Musk has sought to associated himself with the Star Trek universe for many years, and has been partially successful,3 while the founder of virtual reality headset Oculus VR Palmer Luckey has been regularly referred to as ‘a real life Tony Stark’ – Marvel’s tech boss superhero – by his fans and uncritical tech commentators alike. Google even named its cluster manager after the Borg, the totalitarian cybernetic organisms in Star Trek. Zuckerberg’s ‘Metaverse’ comes from sci-fi film Ready Player One, a dystopia he took as a blueprint rather than a warning.

These are not just attempts by geeks paying tribute to fictional worlds they love, but part of an active effort in colonizing our collective imagination. Through science-fiction imagery and dystopian warnings, tech billionaires present themselves as visionary geniuses, the protagonists of their own heroic tales saving humanity from crises they are actively making worse. The Artificial Intelligence hype is a key example of this. By using fear as a marketing strategy, they try to sell AI as both an existential threat and a revolutionary solution, while being among its biggest funders and beneficiaries. Just a few months after Musk signed an open letter saying AI poses ‘profound risks to society and humanity’, he launched his own AI chatbot, Grok. OpenAI’s leaders, meanwhile, have repeatedly ‘warned’ about the dangers of AI while courting investors.

Fear is a powerful emotion to conjure up, especially as these companies regularly fail to provide real-life results or live up to the grandiose promises of what their tech can purportedly achieve. By exaggerating the existential threat posed by AI, tech execs can claim that they are the only people who can safely manage these tools and thus monopolize the booming industry.

A story is being told here, one which, crucially, does not require democratic intervention, and instils the myth that their dominance is inevitable. This far right vision imagines most humans on Earth as subservient to ‘the supremely wealthy, protected by private mercenaries, serviced by AI robots and financed by cryptocurrencies’.4 They are telling us to sit back and trust them, with each iteration resembling more and more the sort of blind faith required by cults and conspiracy theorists, such as QAnon supporters (see page x) who are told to just ‘trust the plan’.

This is what the fear-based approach favoured by these tech bosses relies on, and what it contributes to. And governments are buying into it. These conspiracy fictions are being normalized at the highest levels of governments around the world. Britain’s Labour government for instance recently announced that AI will be ‘unleashed’ and ‘mainlined into UK’s veins’.5 This goes far and beyond merely recognizing that AI tools can have certain uses. It is very much part of a broader effort to sell a story to increasingly sceptical populations.

The challenge we face today is to find ways to stop these bosses, drawn from a tiny elite, from causing additional harm.

These men, or ‘broligarchs’, are increasingly tied up with far right politics, underlined by the presence of Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg, Apple’s Tim Cook, and Google’s Sundar Pichai alongside Musk at Trump’s inauguration. They are putting their corporations at the service of supremacist and authoritarian projects, from facilitating ethnic cleansing of people of colour by United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to Israel’s genocide in Gaza, passing by helping Saudi Arabia become ‘a global hub for AI’ and the Chinese Communist Party identify ethnic Uyghurs.6,7, 8, 9

Storytelling against the fantasy of inevitability

If we’re to confront the tech oligarchs and the reactionary politics they are enabling, what we need is to overcome the ingrained cynicism and nihilism of capitalist culture. We need to give people the opportunity to experience what it’s like when people come together and change the world together. These worlds are already being explored through fiction. What may seem like escapism is in fact an important first step towards building the worlds we want.

Narratives have always shaped what people believe is possible. Scholars call this ‘transportation’, the ‘integrative melding of attention, imagery and feelings, focused on story events’. This is key to understanding how it shapes how we perceive the world, and what we perceive to be ‘realistic’ or ‘unrealistic’ in it. Indeed, research suggests that those who are ‘transported’ can find themselves integrating elements of the story and turning them into ‘real-life beliefs’.10 This is part of the reason why, when confronted with the very real existing and eventual harm caused by AI, many have internalized the story that these tools will nevertheless fix almost everything.

Meanwhile, researchers at MIT found that ‘brain connectivity systematically scaled down’ with the use of AI.11 The very products being wielded to concentrate profits in the hands of a smaller and smaller elite are also limiting our ability to imagine alternatives. Which underlines the urgency of fighting back while we can, with a tool in dire need of reclaiming: storytelling.

Dream big, kid

What we need isn’t more critique. We have seen the AI industries not only able to ignore but even integrate them into the hype they rely on to keep investments pouring in.

Instead, what we need is a real vision of change. Instead of constantly reacting, the left must be part of a wider effort to push the boundaries of what’s considered possible – of imaging a world beyond billionaires, borders and capitalism.

This isn’t utopian naivety, but a recognition that we are all affected by what Mark Fisher called capitalist realism, namely the sense that “it is now impossible even to imagine a coherent alternative to [capitalism],” and that this limitation affects how we interact with one another, and how we build movements together. If we collectively feel that overcoming capitalism is ‘unrealistic’, we act accordingly.

It is that sentiment that the writer Ursula Le Guin challenged when she famously said that ‘we live in capitalism, its power seems inescapable – but then, so did the divine right of kings’.12 Our task today is to make capitalism’s rule seem less and less inescapable – and ultimately as abolishable.

One of the ways to do this is to harness the power of storytelling, to create, share and popularize stories that can uplift one another and defeat those that know nothing more than to plunder this world’s resources to pursue the shallowest of lives.

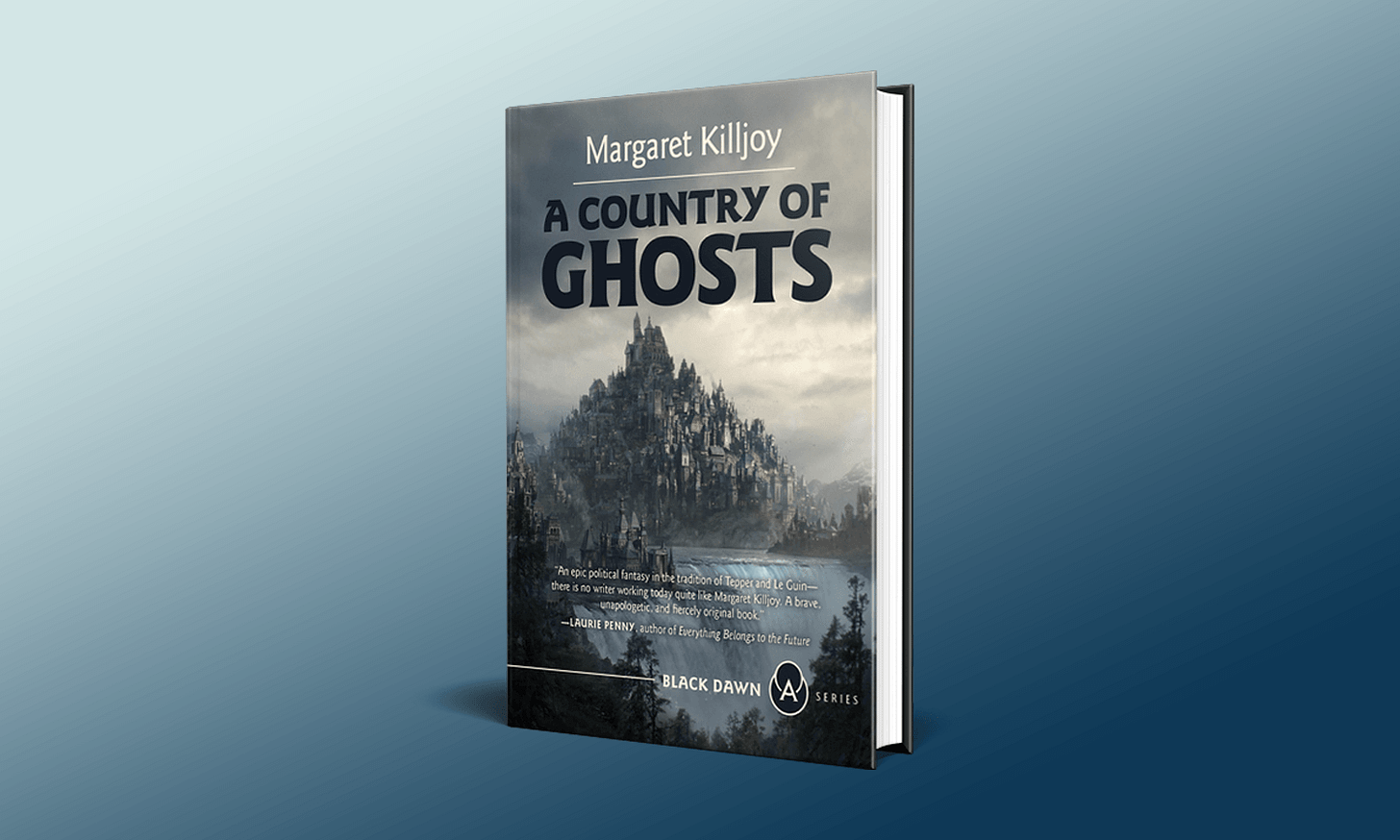

Examples already exist. Margaret Killjoy’s A Country of Ghosts envisions the anarchist ‘country’ of Hron, a society under threat from a colonial empire. Through the eyes of a journalist embedded in Hron’s people, we see how he begins to question many of his engrained colonial beliefs, assumptions that many readers may have themselves.

By transporting the reader to Hron, Killjoy invites them to reorient what feels ‘normal’, a feat only possible through a suspension of disbelief wherein we allow ourselves, for a period of time, to be outside the boundaries of the many realisms governing our own world.

Fiction in this sense is more than just escapism – imagining something different is the first step toward building it.

Reopening the future

In recent years, we have seen a culture of despair set in, and we can see it in the ongoing dominance of post-apocalyptic films as well as in phenomena like ‘doomscrolling’.

But we have also seen a surprising resurgence in radically hopeful stories reach the mainstream, with Star Wars Andor an obvious name to mention here. Leftwing commentators and analysts have been surprised that a story as radical as Andor was approved by the very mainstream Disney+, which is a priority boycott target of the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement targeting Israeli apartheid. The series drew inspiration not just from the anti-Nazi resistance prior to and during World War II, but also from the Algerian National Liberation Front and the Irish Republican Army, and it would not be lost on any Palestinian viewer that the most prominent uprising in Andor, the Ferrix uprising, would be called an intifada in Arabic.

The widespread critical acclaim that Andor has received speaks to an opening amid the many crises of the modern world. There is an appetite for more daring stories, those that centre mutual aid and community organizing among segments of the population that would otherwise shy away from such seemingly radical ideas. The ongoing resistance against ICE immigration raids in the US also demonstrates this. The number of people being radicalized for the first time at the sight of state-sanctioned kidnappings of their neighbours could reasonably reach the millions, especially as the Trump regime shows no sign of slowing down. The job of radical storytellers is to make it easier to imagine not just the end of authoritarian structures like ICE, but also to imagine a world where their very existence would be rendered obsolete.

‘Hayao Miyazaki’s thoughts on an artificial intelligence’, Manhattan Project for a Nuclear-Free World, YouTube, 16 November 2016, a.nin.tl/Miyazaki

Brian Merchant, ‘OpenAI’s Studio Ghibli meme factory…’, Blood in the Machine, 27 March 2025, a.nin.tl/meme

Chris Snellgrove, ‘Star Trek’s worst line…’, Giant Freakin Robot, a.nin.tl/StarTrek

Naomi Klein and Astra Taylor, ‘The rise of end times fascism’, The Guardian, 13 April 2025, a.nin.tl/EndTimesFascism

Robert Booth, ‘Mainlined into UK’s veins…’, The Guardian, 13 January 2025, a.nin.tl/Labour

Caroline Haskins, ‘ICE is paying Palantir…’, The Intercept, 18 April 2025, a.nin.tl/Thiel

Marwa Fatafta, ‘Big Tech and the risk…’, accessnow, 11 October 2024, a.nin.tl/Gaza

Carole Cadwalladr, ‘The dark lord of Silicon Valley’, How to survive the broligarchy newsletter, 2 June 2024, a.nin.tl/MBS

‘China Uyghur analytics…’, Campaign for Uyghurs, 2 December 2019, a.nin.tl/Uyghurs

Melanie C. Green, ‘Transportation into narrative…’, Discourse Processes, Vol 38, 2004, a.nin.tl/NarrativeWorlds

Nataliya Kosmyna et al, ‘Your brain on ChatGPT…’, arXiv, June 2025, a.nin.tl/AI

‘Ursula le Guin’, National Book, YouTube, November 2014, a.nin.tl/kings